Chemical Changes

Chemical changes involve substances reacting to form new materials. These changes are often irreversible and include important processes like neutralisation, metal extraction, and acid reactions. This topic explores the reactivity of substances and how we can use chemical reactions in real-world applications.

Practicals on this page:

Titrations

Acids, Bases and the pH Scale

Acids are substances that release H⁺ ions in solution, while alkalis are soluble bases that release OH⁻ ions.

The pH scale measures how acidic or alkaline a solution is:

- pH 0–6: Acidic

- pH 7: Neutral

- pH 8–14: Alkaline

Indicators like litmus, methyl orange, or universal indicator can be used to determine the pH.

Strong and Weak Acids

- Strong acids (e.g., hydrochloric acid, sulfuric acid, nitric acid) completely ionise in water, meaning they release all their H⁺ ions.

- Weak acids (e.g., ethanoic acid, citric acid) partially ionise, releasing fewer H⁺ ions.

Strength is different from concentration:

- Concentration is the number of acid particles in a given volume.

- You can have a concentrated weak acid or a dilute strong acid.

Reactions of Acids

Acids react with several types of substances to produce salts:

- Acid + Metal → Salt + Hydrogen

- Example: Mg + 2HCl → MgCl₂ + H₂

- Acid + Metal Oxide → Salt + Water

- Example: H₂SO₄ + CuO → CuSO₄ + H₂O

- Acid + Metal Hydroxide → Salt + Water (Neutralisation)

- Example: HCl + NaOH → NaCl + H₂O

- Acid + Carbonate → Salt + Water + Carbon Dioxide

- Example: 2HCl + CaCO₃ → CaCl₂ + H₂O + CO₂

The salt formed depends on the acid and the metal compound used:

- Hydrochloric acid → chlorides

- Sulfuric acid → sulfates

- Nitric acid → nitrates

Revision Notes

The Cornell method is like a supercharged note-taking system that helps you ace your revision!

Print out our blank revision notes pages to help you revise.

How to make effective revision notes with the Cornell method.

Exam Questions & Answers

Download and print off practice our FREE worksheet with exam style questions on Cell Biology.

Making Soluble Salts

You can make soluble salts by reacting an acid with an insoluble base (metal oxide, hydroxide, or carbonate):

- Warm the acid gently.

- Add the base in excess until no more reacts (until the solution is neutralised).

- Filter off the unreacted solid.

- Heat the filtrate to evaporate some water, then leave to crystallise.

This is a required practical in most GCSE specifications.

The Reactivity Series of Metals

The reactivity series lists metals in order of how easily they react, especially with water or acids. A simplified version:

Potassium

Sodium

Calcium

Magnesium

Aluminium

Zinc

Iron

Copper

Gold

Metals above hydrogen in the series react with acids to release hydrogen gas.

The more reactive the metal, the faster and more vigorous the reaction.

Metals Reacting with Acids

More reactive metals react faster and more exothermically with acids. You can observe:

- Fizzing from hydrogen gas

- Temperature increase

- Disappearance of the metal

Less reactive metals, like copper or gold, do not react with dilute acids.

Extracting Metals from Oxides

Many metals are found as metal oxides and must be extracted by reduction, removing the oxygen.

Reduction with Carbon

Metals less reactive than carbon (like zinc, iron, and copper) can be extracted by heating their oxides with carbon. Carbon displaces the metal:

Example:

Redox Reactions

A redox reaction involves both reduction (gain of electrons) and oxidation (loss of electrons).

- Oxidation: Loss of electrons or gain of oxygen

- Reduction: Gain of electrons or loss of oxygen

In metal extraction and displacement reactions, redox processes are always involved.

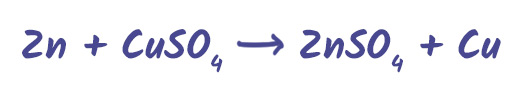

Displacement Reactions

A more reactive metal will displace a less reactive metal from its compound.

Example:

Zinc is more reactive than copper, so it displaces it from the solution.

These reactions help us understand metal reactivity and are common in experiments.

Ionic Equations

Ionic equations show the particles that actually change in a reaction, removing the spectator ions.

Example:

This shows the key ions involved in the displacement reaction without the sulfate ions.

PRACTICAL - Titrations

Titration is used to find out exactly how much acid is needed to neutralise a known volume of alkali (or vice versa). It’s an important technique for making salts and calculating concentrations.

In this practical, an acid is added slowly from a burette into a flask containing a known volume of alkali and a few drops of indicator (like phenolphthalein or methyl orange). The acid is added until the indicator shows that neutralisation has occurred — this is the endpoint.

You then repeat the process to get concordant results (results within 0.1 cm³ of each other), and use the average to calculate the unknown concentration using the titration formula.

Links for Learning

BBC Bitesize: Acids, bases and salts

BBC Bitesize: Reactions of metals

BBC Bitesize: Making soluble salts

Study Mind: The Reactivity Series

BBC Bitesize: Redox reactions

BBC Bitesize: Phytoextraction (phytomining)

BBC Bitesize: Chemical changes quiz

Shalom Education: Displacement Reactions

Revision Notes

The Cornell method is like a supercharged note-taking system that helps you ace your revision!

Print out our blank revision notes pages to help you revise.

How to make effective revision notes with the Cornell method.

Why Do I Need to Know About Chemical Changes?

In Everyday Life

- Understanding how acids and alkalis work in cleaning products and antacids

- Knowing what happens during cooking, burning, or rusting

- Interpreting the pH of water, soil, or skin care products

- Making safe decisions with household chemicals

- Understanding how batteries and fuels work

In Science & Chemistry Careers

- Carrying out titrations and redox reactions in labs

- Using reactivity series to extract or refine metals

- Designing safer chemical processes in industry

- Developing new chemical products like fertilisers or medicines

- Understanding energy transfers in reactions and fuels